Become a Patreon!

Abstract

Excerpted From: Adriane M. Kappauf, Twin Flames: A Story of Racial Gerrymandering and Partisan Gerrymandering, 28 Widener Law Review 119 (2022) (182 Footnotes) (Full Document)

In the immediate aftermath of the appalling attack on the United States Capitol by American insurrectionists and one of the most contentious, unprecedented elections in American history, it seems surreal to imagine Americans finding any speck of agreement in this era of rigid, unmanageable polarization. Ironically, fragile common ground can be found in Americans' consensus that the American experiment is fragile and in decline with diminishing trust in government and each other stoking division. One of the most perplexing questions is where the fracture that ignited this crippling, rapidly-paced divide is. Where is the political extremism coming from? This note focuses on the godfather of political extremism: gerrymandering. Like political extremism, gerrymandering has been with us since 1789, but arguably what is different now is that it has been put on steroids in recent years and left unrestrained. Once again, Americans are surprisingly united on this issue, with over seventy percent of Americans, even across political aisles, agreeing the Supreme Court should intervene to limit its corrosive influence on American democracy.

In the immediate aftermath of the appalling attack on the United States Capitol by American insurrectionists and one of the most contentious, unprecedented elections in American history, it seems surreal to imagine Americans finding any speck of agreement in this era of rigid, unmanageable polarization. Ironically, fragile common ground can be found in Americans' consensus that the American experiment is fragile and in decline with diminishing trust in government and each other stoking division. One of the most perplexing questions is where the fracture that ignited this crippling, rapidly-paced divide is. Where is the political extremism coming from? This note focuses on the godfather of political extremism: gerrymandering. Like political extremism, gerrymandering has been with us since 1789, but arguably what is different now is that it has been put on steroids in recent years and left unrestrained. Once again, Americans are surprisingly united on this issue, with over seventy percent of Americans, even across political aisles, agreeing the Supreme Court should intervene to limit its corrosive influence on American democracy.

However, the Supreme Court has not embraced this rare unison of public opinion and desire for its intervention. In June 2019, the Supreme Court shrugged the growing, corrosive problem of partisan gerrymandering as an elephant in America's room of democracy that is simply too wild and complex to tame and remove, declaring it a nonjusticiable political question. Aside from this landmark decision being the first of its kind for the majority of the Court leaning on the political question doctrine to avoid adjudicating merits of a case solely on the perceived lack of a judicially discoverable or manageable standard, scholars and citizens alike are puzzled by the staggering amount of case law and public opinion vividly illustrating the existence of multiple paths to solving this surging issue.

The Supreme Court has a tumultuous, tangled past with redistricting jurisprudence, especially in exploring the relationship between racial gerrymandering and partisan gerrymandering. While the Court has established clear bright-lines tests on the blatant unconstitutionality of racial gerrymandering, Rucho reflects the reluctance and ambivalence plaguing the Court on partisan gerrymandering. Further mystifying the Rucho decision, the Court ruled in 2017 in Cooper v. Harris that partisanship cannot justify a racial gerrymander while also acknowledging in a previous North Carolina case that racial gerrymandering can also constitute partisan gerrymandering. Gerrymandering cases have been prevalent in the United States, but prior to the Rucho decision, lower federal courts have been wildly inconsistent and developing tests of their own, in the Supreme Court's absence on this issue.

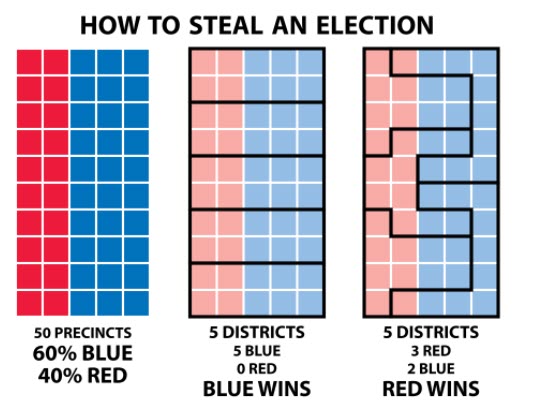

Many notable legal and constitutional scholars have vigorously debated the invalidity of gerrymandering, and it remains extremely unpopular among the American public. One of the leading experts in the legal realm of redistricting jurisprudence, Professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos, asserts that the frequency and intensity of gerrymandering are being facilitated by most election law and redistricting jurisprudence decided in a “Golden Age of Nonpartisanship” of the 1970s-the 1980s that is the polar opposite of the hyper-partisan climate America is currently experiencing. American election and redistricting law needs a tune-up to match the currency of the times. Further exacerbating the hyper-partisan climate, the emergence of highly sophisticated mapping technology, such as MAPTITUDE, has also made targeting voters with surgical precision require no more effort than the click of a mouse. Such technological innovations have also given rise to the dark arts of “cracking and packing,” making it simple to divide voters of one party (cracking) across multiple districts while also concentrating voters of one party into a district (packing) to create a practically impossible hurdle for the opposition to mount and an insurmountable electoral advantage for the packers and crackers.

While these new developments have made serious contributions to the new trends in gerrymandering, race being deeply intertwined with political identity is not new. Racial gerrymandering is typically remedied by the “crown jewel” of the Civil Rights Movement in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). However, with the Supreme Court defanging the VRA in 2013 in Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder by abolishing the requirement for states traditionally fond of Jim Crow laws to submit their districting maps to the Department of Justice for an approval process known as preclearance, as mandated by Section Five of the law, voter manipulation by race masquerading as partisan gerrymandering was unleashed almost immediately. Emboldened by the lack of restraint, the Arizona legislature took its own citizens to court to overturn the will of the citizens who voted on a ballot initiative to permit an independent commission to draw constitutionally permissible congressional district maps. Once given the power to write and grade their own exams by choosing their voters, rather than voters choosing their candidates, legislatures have revealed they cannot police themselves. Many state legislatures have found increasingly creative ways to disguise their motives as partisan gerrymandering, rather than racial, despite the Bush v. Vera decision specifically prohibiting this practice.

Typically claims for racial gerrymandering are brought under Fourteenth Amendment equal protection violations or First Amendment freedom of association violations. However, Rucho v. Common Cause asserted that while gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles,” the traditional routes of the First Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment are no longer viable vehicles to success. With state legislatures having no motive to correct a problem that they profusely benefit from, the judiciary is the last line of defense with this unique problem that is only growing. Not only was gerrymandering to toxic extremes anticipated by the Founders, judicial intervention to protect the integrity of a free and open democratic society is engrained in the oath and sacred birthright the Supreme Court takes with “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.”

The purpose of this note is to illuminate that the Court needs to look no further than its own precedent to discover one of many routes to a workable solution, even if it is hidden in plain sight. The goals of racial and partisan gerrymandering are the same malice to be confronted: diminishing the weight of one group of citizens' constitutional rights with state power to participate fully in the political process. The Court has demonstrated its willingness to exercise discretion with racially gerrymandered cases being justiciable and even going as far as partisan gerrymandering being racial gerrymandering. As scholars have noted, election law is outdated and not up for the challenge of confronting these modern redistricting issues effectively, especially as technological development outpaces human adaption to it, and new, robust challenges require new, innovative solutions.

With the force of the Voting Rights Act diminished, the incentive for Congress or state legislatures to insulate the problem, and the First and Fourteenth Amendment challenges invalidated, a new frontier to combat this problem lies in the often ignored but robust Fifteenth Amendment. Little jurisprudence, if any in the modern era, exists under this doctrine, partly because it has been blatantly ignored for most of its history, as evidenced in Jim Crow laws forcing Congress and President Lyndon B. Johnson to move swiftly to enact a robust Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Congress updating and renewing the legislation, until recently. Relying on the Court's own words just a few years ago, “If legislators use race as their predominant districting criterion with the end goal of advancing their partisan interest, their action still triggers strict scrutiny,” which implies racial gerrymandering doctrine can be activated to combat partisan gerrymandering. The implication is clear: race and party are intertwined, and state legislators hiding behind partisan gerrymandering to disguise a racial motive is impermissible.

The Supreme Court has already arrived at the result, but their lack of agreement or willingness to decide on a method does not mean one does not exist. A Fifteenth Amendment violation for diluting votes based upon race is a new landscape that could provide a fresh outlook from the Court's convoluted past with this issue. Further, it can be bolstered by borrowing tests from the lower courts, most notably Pennsylvania in League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth, which had their Supreme Court approve, with outside assistance, the state's districting maps, similar to the Voting Rights Act Section Five requirement. Shaw v. Reno from 1993 provides the framework that “bizarrely shaped districts” are strongly indicative of racial intent, and Miller v. Johnson adds that if race is a predominant factor in the drawing of the lines, then it is unconstitutional. Using this combination of precedent for a Fifteenth Amendment claim, the court recognized that the most extreme gerrymandering cases are inherently intertwined with targeting race (Easley v. Cromartie), and ruling independent commissions do not violate the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission), if the Court finds a Fifteenth Amendment violation, it can mandate the implementation of an independent commission supervised by State Supreme Courts. If the dark arts of drawing districts to dilute minority voters can be accomplished with advanced mapping software, then independent commissions can utilize them for the common good too. All of the scattered pieces for a justiciable, workable solution are all present, just awaiting the Court to connect the puzzle.

The Note begins with a brief explanation of redistricting doctrine, the definition of gerrymandering, and the Court's relationship to partisan gerrymandering versus racial gerrymandering. A brief overview of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its role in the jurisprudence is also necessary to paint the picture of the Rucho decision. While the entirety of this Note attempts to illuminate the urgent necessity for judicial intervention with a new outlook on adjudicating this problem as it metastasizes as a threat to democracy, the last part concludes with a suggested solution of the Fifteenth Amendment as a vehicle to solving this complex problem and how the Court's own precedent provides the roadmap.

[. . .]

A vital principle of democracy is being crippled by the growing, urgent problem of partisan gerrymandering disguising racial motivations. Voters are no longer selecting their candidates in free and fair elections, but rather, candidates are targeting their own voters by manipulating the system to remain in power. Holes left in Rucho precedent are creating confusion and inconsistency and allowing the one evil they have clearly prohibited, racial gerrymandering, to ravage the electoral process of the United States. To remedy these problems, the Supreme Court should take the opportunity to clarify a clear standard for all states to implement that mirrors what the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Supreme Court did in approving maps with independent commissions. With Congress uniquely unqualified to act in the best interest of voters, due to a severe conflict of interest, the Supreme Court is the last line of defense in stifling political extremism and racism in the political process.

J.D. Candidate, 2022, Widener University Delaware Law School

Become a Patreon!