Abstract

Excerpted From: Keith D. Yamauchi, Without Due Process: The Eagle and the Beaver the Past, the Present, 30 Asian American Law Journal 3 (2023) (369 Footnotes) (Full Document)

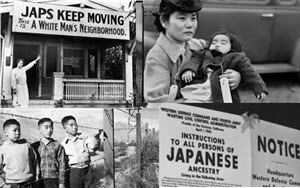

On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service bombed Pearl Harbor on the Island of O'ahu, in the Territory of Hawai'i. The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan. In his speech, he said that December 7, 1941, will be “a date which will live in infamy” and that he, as Commander in Chief, “directed that all measures be taken for our defense.” So began the American involvement in World War II against Japan. On that same date, Canada issued a proclamation of war between Canada and Japan.

On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service bombed Pearl Harbor on the Island of O'ahu, in the Territory of Hawai'i. The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan. In his speech, he said that December 7, 1941, will be “a date which will live in infamy” and that he, as Commander in Chief, “directed that all measures be taken for our defense.” So began the American involvement in World War II against Japan. On that same date, Canada issued a proclamation of war between Canada and Japan.

On May 6, 1942, a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) arrived at the front door of the farmhouse that Denjiro Okabe owned in Mission, British Columbia. Mr. Okabe came to Canada in 1907, and his wife, Taki, arrived ten years later as a “picture bride.” Their children were Canadian citizens, having been born in Canada. The officer told Mr. Okabe that he and his family had twenty-four hours to vacate their farm and that each family member could take only one suitcase. The next day, the RCMP officer returned. When Mr. Okabe's youngest daughter, Yoshino, asked the RCMP officer if she could take her dog with her, the officer pulled out his firearm and shot the dog.

The RCMP took Mr. and Mrs. Okabe and their six children to an “Assembly Centre” located at the Hastings Park Exhibition Grounds in Vancouver. They lived in cattle stalls with other families. The family eventually boarded a cattle car that took them to a sugar beet farm in Picture Butte, Alberta, where the entire family lived in a one-room, uninsulated sugar beet shed. They worked as farm laborers and were given just enough money to buy some food and clothing.

Denjiro Okabe was my grandfather, and his youngest daughter, Yoshino, is my mother. My grandfather died in 1964 at the age of 78. I never spoke to him about his experiences. He spoke no English, and I spoke no Japanese. He was harassed by non-Japanese people when he tried to speak English, so he stopped trying. I spoke no Japanese, because my mother did not want her children to be seen as “non-Canadian.” She thought the Canadian government would punish us if we were not “Canadian.” And she never talked about her wartime experiences.

The Okabe family would never return to their farm in Mission, British Columbia. At the end of the war, the British Columbia Security Commission told Mr. Okabe that the Canadian government had sold his farm “to pay for the cost of moving all you Japs from here and detaining you.” Mr. Okabe received no compensation.

On February 19, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford signed Proclamation 4417, formally terminating the executive order that resulted in the forced removal of the Japanese from the West Coast. In his address to the nation, he said, “We now know what we should have known then--not only was that evacuation wrong but Japanese-Americans were and are loyal Americans.” But does the non-East Asian majority really know that, and do they really believe that the evacuation was wrong? More broadly, does this “knowledge” do anything to stop racial discrimination against persons of East Asian ancestry?

This Article discusses the systemic racism that persons of East Asian ancestry faced in the United States and Canada from the moment their ships began landing on North American shores in the middle of the nineteenth century. Although each country differed in their respective constitutional underpinnings and approaches, the results were substantively and substantially the same. This Article begins with examining the direct and indirect ways in which the legislatures and courts sought to quell the arrival and settlement of the Chinese in the mid-1800s, followed by the Japanese in the latter part of the nineteenth century on the West Coast of North America. Although there were no evidence or factual bases that pointed to East Asian people being a burden or threat to the non-East Asian majority, some non-East Asians wanted them removed from the West Coast. And Pearl Harbor provided the perfect opportunity to remove some of them.

Part I begins with a brief discussion of constitutional and normative differences between the American and Canadian landscapes. Part II examines the migration of the Chinese and Japanese to North American shores and the de jure and de facto discrimination they faced on their arrival. Part III contains a discussion of the evacuation and internment of the Japanese and how each country achieved the same result through different means. This Part also contains an analysis of the three important American cases in which citizens attempted to exercise their constitutional rights. Part IV concludes that the evacuation of the Japanese during World War II was not just a reaction to the hysteria of war, but part of a carefully orchestrated effort toward the removal of East Asian peoples from the West Coast that began on their arrival. It hypothesizes that the anti-Asian sentiment that began in the middle of the nineteenth century continued through the twentieth century and beyond.

[. . .]

The pain that East Asians endured throughout the period before World War II, and the treatment of Japanese-American and -Canadian citizens during World War II, epitomize the reprehensible consequences of normalizing racism at the systemic level. These decisions will live in infamy. Just as the bombing of Pearl Harbor produced the concurrence of de jure and de facto racism, the deep and continued presence of individual and systemic racism still threaten to move us toward legislated and jurisprudential racism. And with the flexible way in which the American courts interpreted the U.S. Constitution when its citizens most needed its protection, the aegis of the Charter and the U.S. Constitution might simply be a hollow bundle of rights. As Professor Daniels wrote, “While most optimists would argue that, in America, concentration camps are a thing of the past--and one hopes that they are--many Japanese Americans, the only group of citizens ever incarcerated simply because of their genes, would argue that what has happened before can surely happen again.”

We hope that this will never happen again. However, given the way we have reacted during times of real or perceived threat--whether that threat manifests itself through a gun barrel, job loss, or an inexplicable virus--the danger of history repeating itself remains ever-present. Uncertainty exists.

Justice of the Court of King's Bench of Alberta, B.A. (Calg.), LL.B. (Sask.), LL.M. (B.C.).